You Won’t Believe These Hidden Festival Vibes in Ziguinchor

Have you ever stumbled upon a celebration so alive, so full of color and rhythm, that it rewires your soul? That’s exactly what happened when I wandered into Ziguinchor, Senegal. Far from the usual tourist trails, this riverside gem bursts with cultural energy during its local festivals—drumming that shakes your chest, dances that tell ancient stories, and communities opening their hearts. It’s raw, real, and absolutely unforgettable. Nestled in the lush southern region of Casamance, Ziguinchor offers a travel experience defined not by luxury resorts or curated itineraries, but by human connection, tradition, and the deep pulse of West African life. For travelers seeking authenticity, this is where the journey becomes transformation.

Discovering Ziguinchor: Beyond the Beaten Path

Situated along the banks of the Casamance River, Ziguinchor stands apart from the more familiar rhythms of northern Senegal. This quiet city, the capital of the Ziguinchor Region, unfolds at a gentle pace, where life moves with the tides and seasons rather than schedules and traffic. Unlike the bustling coastal hubs like Dakar or Saly, Ziguinchor remains largely untouched by mass tourism. There are no sprawling beachfront hotels or international chains lining the waterfront. Instead, visitors find modest guesthouses, family-run restaurants, and a landscape painted in vibrant green—dense mangroves, rice paddies, and towering palm trees swaying in the tropical breeze.

The region's geographical isolation has contributed to its preservation. Separated from northern Senegal by The Gambia, Casamance has developed its own cultural identity, shaped by the Diola (Jola), Mandinka, and Pulaar peoples. Their traditions, languages, and spiritual practices have flourished with less outside influence, creating a space where ancestral customs remain central to daily life. The red laterite roads winding through villages, the scent of grilled fish and woodsmoke in the air, the sight of women balancing baskets of fruit on their heads—these are not staged for tourists. They are the everyday fabric of a resilient, proud community.

Ziguinchor’s relative obscurity is not due to a lack of beauty or significance, but rather to historical circumstances and limited infrastructure. While peace has largely returned to the region after periods of political tension in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, tourism development has remained cautious. This has inadvertently protected the area’s authenticity. For the mindful traveler, especially women between 30 and 55 who value meaningful experiences over convenience, this presents a rare opportunity. Here, travel is not about ticking off landmarks, but about slowing down, observing, and connecting. It is a destination where curiosity is rewarded with warmth, and where cultural immersion happens naturally, not through paid performances.

The Heartbeat of Casamance: Festival Culture in Ziguinchor

Festivals in Ziguinchor are not spectacles designed for outsiders—they are vital expressions of community, spirituality, and continuity. Rooted in agricultural cycles, rites of passage, and ancestral reverence, these gatherings are deeply woven into the social fabric of Casamance. Unlike commercialized cultural shows, which often reduce tradition to entertainment, local festivals in Ziguinchor are participatory, spontaneous, and sacred. They are moments when generations come together to honor the past, celebrate the present, and ensure the survival of their heritage.

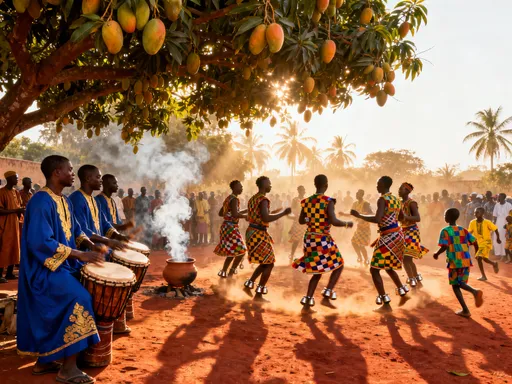

Music and dance are at the core of every celebration. The hypnotic rhythms of the djembe and dunun drums echo through the villages, summoning people from surrounding areas. The balafon, a wooden xylophone with gourd resonators, weaves melodic patterns that seem to speak directly to the soul. The kora, a 21-stringed harp-lute, is often played by griots—oral historians who preserve genealogies, proverbs, and legends through song. These instruments are not merely for performance; they are spiritual conduits, believed to carry messages to the ancestors and invoke blessings for the community.

Dance troupes, often composed of youth trained from childhood, wear elaborate costumes made of raffia, beads, and hand-dyed cloth. Their movements are not choreographed for aesthetic appeal alone, but serve as storytelling devices—reenacting myths, historical events, or natural phenomena like the flight of birds or the swaying of trees. Masks, sometimes representing spirits or animals, appear in certain ceremonies, particularly those linked to initiation or harvest. These are not costumes to be worn lightly; they carry spiritual weight and are treated with deep respect.

What makes these festivals so powerful is the absence of separation between performer and audience. There is no stage, no ticket, no designated viewing area. When the drums begin, everyone is invited—children, elders, visitors—to join in the circle. Participation is not mandatory, but those who choose to move with the rhythm, even clumsily, are welcomed. This inclusivity reflects a fundamental value in Casamance culture: community as family. For a traveler, especially one seeking emotional resonance and personal growth, this level of integration is profoundly moving. It is not tourism as observation, but as belonging—even if only for a day.

Timing Your Trip: When the Magic Happens

Planning a visit to Ziguinchor around its festivals requires patience, flexibility, and a willingness to embrace the unpredictable. Unlike fixed-calendar events in Europe or North America, many traditional celebrations in Casamance are tied to agricultural cycles, lunar phases, or community needs. Dates are often confirmed only weeks in advance, communicated orally or through local networks. This means that rigid itineraries are unlikely to capture the true essence of the experience. Instead, travelers are encouraged to allow ample time—ideally two to three weeks—and remain open to last-minute invitations.

The best window for festival travel is the dry season, which runs from November to May. During these months, the rains have subsided, roads are more passable, and communities are actively engaged in post-harvest celebrations. December through February is particularly vibrant, as many villages host annual festivals to give thanks for the rice and millet harvests. These events often include communal feasting, ritual offerings, and multi-day dance ceremonies. Some of the larger gatherings may coincide with national holidays or regional cultural weeks, when local governments support traditional events to promote heritage tourism.

For those seeking a more structured approach, it is advisable to connect with local cultural associations or community-based tourism initiatives before arrival. Organizations such as the Association pour le Développement du Tourisme Communautaire en Casamance (ADTCC) often maintain informal calendars of upcoming events and can facilitate introductions to village elders. Hiring a local guide upon arrival in Ziguinchor is another effective strategy. These guides, often bilingual in French and Diola, serve as cultural interpreters, helping visitors navigate etiquette, language barriers, and unspoken rules.

It is important to understand that not all festivals are open to outsiders. Some, particularly those associated with initiation rites or spiritual ceremonies, are reserved for members of the community. Respect for these boundaries is essential. Pushing to attend a private event can damage trust and disrespect local values. However, many celebrations—especially those marking harvests, naming ceremonies, or seasonal transitions—are welcoming to respectful guests. The key is to arrive not as a spectator, but as a humble learner, ready to listen and adapt.

A Day at a Local Festival: What to Expect

Imagine waking before dawn to the sound of distant drums pulsing through the humid air. Smoke curls from cooking fires as women prepare large pots of thieboudienne, Senegal’s national dish of fish and rice, along with bowls of spicy peanut stew and plantains. Chickens dart between huts, and children run barefoot, their faces painted with white clay for protection and celebration. Elders gather beneath the shade of a baobab tree, dressed in flowing boubous, sipping sweet mint tea and discussing the day’s rituals. This is how a festival day begins in a village near Ziguinchor—not with fanfare, but with quiet preparation, a sense of sacred duty.

By mid-morning, the energy begins to build. Drummers warm up in circles, testing rhythms that will later unify hundreds of dancers. Youth rehearse intricate steps, their feet kicking up red dust, while elders supervise with nods of approval. Women carry trays of food to a central gathering space, often a cleared field or village square. The air fills with laughter, conversation, and the occasional burst of song. Visitors are offered water, fruit, or a small cup of palm wine, a gesture of hospitality that signals inclusion.

As the sun reaches its peak, the main ceremony commences. A procession forms—elders first, then dancers, then musicians—moving in a slow, deliberate rhythm toward the sacred site, which might be a family compound, a riverbank, or a grove of trees. The drumming intensifies, layering complex polyrhythms that seem to vibrate in the chest. Dancers, adorned in raffia skirts and beaded headdresses, enter a trance-like state, their movements fluid and powerful. Some wear masks representing ancestral spirits, their presence believed to bless the community and ward off misfortune.

At the height of the celebration, the entire village—men, women, children, guests—joins in a circular dance, moving counterclockwise, clapping, singing, and stomping in unison. The rhythm becomes hypnotic, the heat intense, but no one seems to tire. This is not entertainment; it is a communal act of devotion, a reaffirmation of identity and continuity. For an outsider, the experience can be overwhelming in the best possible way—a sensory and emotional flood that dissolves the usual barriers between self and other. There are no barriers to participation. A smile, a willingness to follow the steps, even a hesitant clap, is enough to be welcomed into the circle. In that moment, language, nationality, and age fall away. What remains is pure human connection.

How to Experience It Right: Etiquette and Engagement

Respect is the foundation of any meaningful cultural exchange, and this is especially true in Ziguinchor. Visitors are guests in a living tradition, not customers at an attraction. Simple gestures of courtesy can make the difference between being tolerated and being embraced. The first rule is to ask before taking photographs, especially of elders, masked dancers, or ritual objects. In many communities, the camera is seen as intrusive, and images are believed to capture more than just likeness—they may disturb spiritual energy. If permission is granted, a small token of appreciation, such as a bar of soap or a packet of tea, is often appreciated.

Dress modestly. Women should wear loose-fitting clothing that covers shoulders and knees. Bright colors are welcome, but revealing attire is inappropriate and may cause offense. Greeting elders first, preferably in French or a few words of Diola, demonstrates respect for hierarchy and tradition. A simple “Salut, comment allez-vous?” or “Ma n’diama” (I greet you) goes a long way. Accepting food or drink when offered is not just polite—it is a sign of trust and inclusion. Refusing may be interpreted as rejection.

Hiring a local guide is one of the most effective ways to engage respectfully. These individuals do more than translate—they explain context, prevent misunderstandings, and ensure that visitors contribute positively to the community. Many guides are affiliated with cooperative lodges or cultural centers, meaning fees directly support local families. Supporting community-run guesthouses, purchasing handmade crafts, and eating at family-owned restaurants are other ways to ensure that tourism benefits the people who welcome you.

Perhaps the most important form of engagement is presence. Put the phone away. Listen to the stories. Learn a dance step. Share a meal. These small acts build bridges far stronger than any photograph. The festivals of Ziguinchor are not performances to be consumed, but relationships to be honored. When approached with humility and openness, they offer not just memories, but transformation.

Getting There and Around: A Traveler’s Guide

Reaching Ziguinchor requires a bit more effort than typical tourist destinations, but the journey itself adds to the sense of adventure. The most direct route is a one-hour flight from Dakar, operated by Air Senegal. Flights are affordable and reliable, though schedules can change. For those who prefer a scenic overland journey, an overnight bus from Dakar takes approximately eight to ten hours, passing through the peanut basin and crossing into Casamance via a ferry at Farafenni, in The Gambia. This route offers a gradual immersion into the region’s changing landscapes and rhythms.

Once in Ziguinchor city, local transportation consists mainly of taxi-brousse (bush taxis)—shared minibuses that travel fixed routes to surrounding villages. They are inexpensive and efficient, though seating is tight and departures are based on passenger load rather than timetables. For riverine communities, pirogues—long, narrow wooden canoes powered by outboard motors—are the primary mode of transport. These boats glide through mangrove channels and across the Casamance River, offering breathtaking views of birdlife, rice fields, and riverside villages. Travelers should plan for delays and embrace the unhurried pace; punctuality is less important than presence in this part of the world.

Accommodation options range from simple but clean guesthouses to eco-lodges run by local cooperatives. Many lodgings offer homestay experiences, where guests eat with host families and participate in daily activities. These stays provide deeper cultural insight and foster personal connections. While amenities may be basic—shared bathrooms, intermittent electricity, no air conditioning—the comfort comes from hospitality, not luxury. Bringing a flashlight, insect repellent, and a reusable water bottle is recommended.

Health and safety are generally not major concerns for travelers. The region is stable, and locals are welcoming. However, it is wise to consult a travel clinic before departure, ensure routine vaccinations are up to date, and take precautions against malaria. Drinking bottled or filtered water, eating well-cooked food, and using sunscreen are standard practices. The most important preparation, however, is mental: come with patience, flexibility, and a willingness to adapt. This is not a destination for those seeking convenience, but for those seeking meaning.

Why Hidden Festivals Matter: Travel That Transforms

In an age of curated Instagram moments and all-inclusive resorts, the festivals of Ziguinchor stand as a powerful reminder of what travel can truly be. They are not about luxury or leisure, but about connection—between people, between generations, between the living and the ancestors. They challenge the notion that tourism must be passive, reminding us that the most profound experiences come not from watching, but from participating.

For women in their 30s, 40s, and 50s—many of whom balance family, career, and personal growth—such journeys offer rare opportunities for renewal. Stepping into a drum circle, sharing a meal with a village elder, learning a dance that has been passed down for centuries—these moments quiet the noise of daily life and reconnect us to something deeper. They remind us of our shared humanity, our capacity for joy, and our need for belonging.

Moreover, choosing to travel this way has broader significance. By supporting community-based tourism, visitors help preserve traditions that might otherwise fade. They empower local economies, validate cultural pride, and foster mutual respect. In a world where globalization often erases difference, these small acts of engagement become acts of resistance—against homogenization, against exploitation, against the idea that travel is merely consumption.

The festivals of Ziguinchor do not change the world with headlines or protests. They change it quietly, one heart at a time. They invite us to slow down, to listen, to open our hands and our hearts. They remind us that the most beautiful destinations are not places on a map, but moments of connection that linger long after the journey ends. So pack your bags with curiosity, your spirit with humility, and your soul with readiness. Because when the drums call in Ziguinchor, they are not just summoning dancers—they are calling you home.